This is the first in the series of essays, Of Sex, Gender and Archetypes on how women’s movements have evolved significantly from the time of their genesis

“When male creatures indulge in their fighting propensity to kill one another, Nature connives at it, because, comparatively speaking, females are needful to our purpose, while males are barely necessary. Being of an economic disposition she does not specifically care for the hungry broods who are quarrelsomely voracious and who yet contribute very little towards the payment of Nature’s bill. Therefore in the insect world, we witness the phenomenon of the females taking it upon themselves to keep down the male population to the bare limit of necessity.” —Rabindranath Tagore

Author’s note:

In 2005, Larry Summers, the then President of Harvard University had in an address, dwelt extensively on the probable causes for low representation of women in math and science. In what was a provocative lecture, Mr. Summers highlighted “My point was simply that the field of behavioral genetics had a revolution in the last fifteen years, and the principal thrust of that revolution was the discovery that a large number of things that people thought were due to socialization weren’t.”

This event triggered an inquiry within my being. Was there scientific truth in what Mr Summers proclaimed? Or was it a derogatory talk filled with gender bias for which he was admonished by the media? I thought of these issues for long but the pressures of a corporate job ensured it was relegated to the long-term parking lot.

In 2018, after stepping out of the boundaries of corporate life, and while participating in the Radical Transformation Leadership (RTL) program, the topic of gender relations re-emerged and participants were provided with several tools to deal with disempowering isms. In the following two years, as part of my continuing education, I enrolled in the course on systems thinking from eCornell and the Capra Course, which endowed me with a systems view of life. In short, a systems view of life is the ability to search for patterns of connection between the biological, cognitive, social and ecological dimensions of life. These frameworks combined provide one significant insights into dealing with the wicked challenges of our times.

These essays have as their underlying theme relations between the sexes and genders and have as their focus, both women and feminists. We should note that all women are not feminists; in fact many do not identify themselves as feminists and some even oppose feminism. Correspondingly there are men who are highly supportive of women’s movements who could be termed as feminists.

My purpose in writing this three-part article is to table some of the positive achievements of women’s movements; highlight the main issues in the current debate as well as unearth some blind spots and share insights into how these movements can be a greater force to create harmony and help tap our full potential.

Writing on this topic has been arduous because of its vastness and its being densely nuanced. Feminism means different things to different people and when we shift the prism from local to universal, the topic becomes exponentially complex. I was advised to abandon publishing this article because I was told no matter what I wrote on this subject, I was going to be bashed up. This reveals just how polarised this space is. As someone committed to oneness and harmony, I have gone ahead to publish this article with full awareness of the risks. If I fail in achieving what I have set out to at least there wouldn’t have been a failure to try. I should also clarify that this set of essays are in no way intended to convey a definite picture of reality but rather serve as a springboard for healthy conversations on this subject.

When push came to shove, these essays wouldn’t have been penned had it not been for the gracious inputs received from a conversation series I held with Dr Hélène Liu between Oct ’22 and March ’23 on the interconnections between sex, gender and archetypes. I also owe my gratitude to Paramita Banerjee, an Ashoka Fellow and Founder of gender-justice NGO Diksha as well as Sudarshan Rodriguez, my teacher, friend, philosopher and guide. I am indebted to all three for their reviews and precious feedback. I cannot however claim that any of the three would endorse everything that is presented in these essays.

Prologue

We have long forgotten our common ancestor. Life started with a single-cell bacteria, an organism while capable of reproducing, lacked and still lacks any trace of binary sex as is understood today. As living systems evolved and assumed greater complexity, the need for vital biological distinctions became necessary. Today, the human genome consists of roughly 20,000 genes of which about one-third are expressed differently for females and males. When we take a hard look at the human species, both females and males — at the level of biological constituents — are more similar than different.

Feminism and its Evolution

Let’s move fast forward from the inception of life to the mid-nineteenth century. It began with the struggle for women to be granted the right to vote, to own property, the right to education and to break out from being homebound to being seen, recognised and accepted in the mainstream. This was America and its former coloniser Great Britain, and women’s movements spread rapidly all over the Anglo-Saxon world.

To be clear, the genesis of feminism lay in the pursuit by women for equality with men but it has since evolved dramatically. What started off as a movement for the welfare of White women has extended to every woman on planet Earth. Feminist literature points to four distinct waves in women’s struggles, and the journey isn’t over yet.

The first wave, which lasted from mid 1800s to 1920 witnessed significant legislative changes such as adult franchise for women. However, the rights of women of colour were pretty much side-lined in this period.

The Suffragettes fought vehemently for women’s rights, more specifically, the right to vote

Image credit: Harper’s BAZAAR

The second wave occurred between the 1960s and 1980 in which the dominant struggles by women were to seek full equality at the workplace through equal pay for equal work; fight for sexual liberation through access to contraceptives, abortion and childcare support and attain freedom from intimidation and violence. It was in this wave that universal suffrage was extended to all women of colour. By the mid-1970s to early 1980s, women’s struggles for liberation had spread beyond the Western world to low and middle-income countries too.

The third wave which lasted from the 1990s till 2012 saw women’s studies being formally introduced in academia. This wave saw the surfacing of the term Queer theory. ‘Queer’ is an umbrella term used to refer to the spectrum of non-dominant gender identities and sexual preferences that were kept in the shadows for a very long time. The notion of gender extended beyond cisgender, i.e., a gender identity matching with the biological sex assigned at birth. Transgender signifies a broad category that refers to gender that does not match the identify of their biologically assigned sex while transexual refers to those who have undergone sex change through hormone therapy and/or gender reassignment surgery. Queer theory opened up the space for sexual orientations and practices different from the dominant heterosexuality covering a wide range of sexual identities such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, pansexual, asexual, etc.

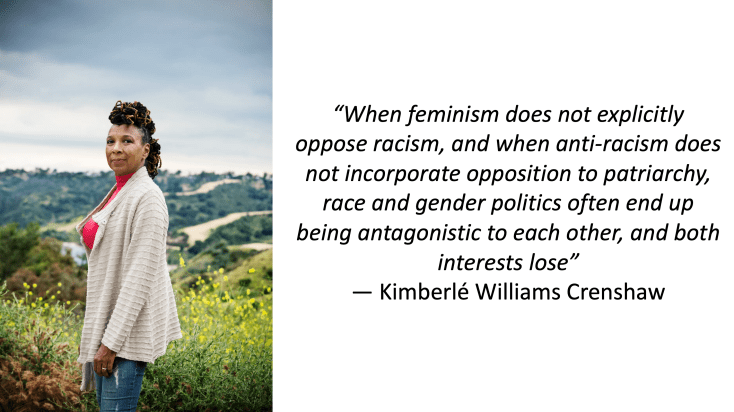

One of the most interesting developments that transpired was the coinage of ‘intersectionality’ by American law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, a proponent of Critical Race Theory. She used this to describe multiple facets of an individual’s identity that resembled intersections on a road. Common to all of these aspects was the endeavour to communicate how different systems intersect to shape oppression of various types and at different levels.

Image credit: asianart.org (adapted)

Often misunderstood, intersectionality encompasses the struggles of all people regardless of gender, sexual orientation, skin colour, ethnicity, religion, caste, culture and lifestyle. To make it contextual, Black women identify both as Black and women, or Indian Dalit women identify as both women and lower caste and their identities intersect at the junction of gender and race or gender and caste. Because they are Black women or Dalit women, they are subject to forms of discrimination that Black men, or White women or upper caste Indian women and men may not.

The fourth wave of feminist movements began in 2013 and remains current. This wave has seen the birth of movements like #MeToo and allied protests such as #BlackLivesMatter. If the third wave introduced intersectionality, the fourth wave saw intersectionality move out from the closets of academia into society with some universal values such as oneness, dignity and self-esteem underpinning it. The fourth wave also saw the participation of men in these movements.

Image credit: Samantha Sophia on Unsplash

The Turning Point

For much of feminism’s history, women’s struggles were the struggles of cisgender women, by cisgender women and for cisgender women. The third and fourth waves of feminist movements witnessed the shift to look beyond cisgender and to pitch a more inclusive agenda that involved transgender and transexual people. Today, the narrative has shifted from biological sex to gender.

This metamorphosis is made amply clear by global feminist champion, Scarlett Curtis, author and editor of the compendium, ‘Feminists Don’t Wear Pink and other lies’ when she writes, “the goal of the feminist movement aims to give each person [italics inserted by author] on this planet the freedom to live their life the way they want to live it, unhindered by sexism or oppression or aggression.”

The shift in paradigm from feminism to humanism is noteworthy. Humanism means an embrace of a broader set of universal values. Does this then do away the debate on sex and gender?

To read part II of this series, The Systems of Oppression please click here

To read Part III of this series, Transcendence and The Quest for Unity please click here

*****

Shakti Saran is a systems thinker, writer, consultant, and the Founder of Shaktify, an initiative to power changemakers

Feature Image Credit: Canva Stock

Discover more from Shakti's Musings: Blogs on everything under the sun

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.